1. Introduction

1.1 What is the Ethereum Name Service (ENS)?

Most people probably first learn about the ENS from seeing people having .eth names as their twitter account name, for example vitalik.eth. The smart contracts of the ENS make it possible to resolve such a name as vitalik.eth to some registered Ethereum address (currently it resolves to: 0xd8da6bf26964af9d7eed9e03e53415d37aa96045). This is a very useful feature for all users of Ethereum and most common web3 applications, such as MetaMask or DeBank already have it integrated. However, while the resolution of names to Ethereum addresses is currently the biggest application of ENS, it’s by far not the only use case. Among other things the ENS also allows your name to resolve to

- crypto addresses of other blockchains,

- content hashes (hashes for IPFS, Skynet, and Swarm, and Tor .onion addresses),

- contract interfaces (ABIs),

- or any text-based metadata.

This article aims to give an introduction to the ENS for blockchain developers by going through the smart contracts lying at the core of ENS. First, we are going to explore the basic building blocks of the system. Afterwards, we dig deeper into the workings of the so-called permanent registrar, which is responsible for handing out .eth names to Ethereum users.

1.2 The Big Picture

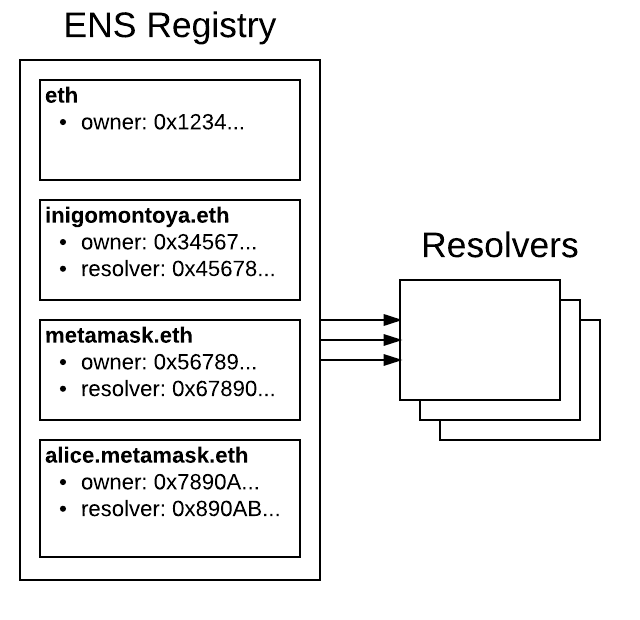

Before we dive deeper, let’s take a bird’s-eye view of ENS. The most fundamental component is the ENS registry, which stores data about names and in particular can determine the responsible resolver for each name. The registry is a single smart contract, but in principle there can be many active resolvers in the system. A resolver fulfills a very similar task as a DNS resolver: When it receives a name, it responds by returning the associated resource, which, in the simplest case would be an Ethereum address. Lastly, there are registrars, which are smart contracts responsible for allocating subdomains. Similar to resolvers, there can be many registrars and they can exist at any level of the hierarchy. For example, if you own the name “alice.eth” it means you can deploy your very own registrar contract and transfer to it the ownership of your domain. This contract can then be used to issue subdomains of the type x.alice.eth to users and you can freely make up the rules for who gets a subdomain. But since we are getting ahead of ourselves, we will come back to this topic later.

2. The Core Contracts of the ENS

2.1 Names and Nodes

The smart contracts of the ENS revolve around the concept of a node, which in this context is defined as a hash uniquely identifying a name. A name, in turn, is an ENS identifier such as “alice.eth”, which can be composed of multiple labels, each separated by a dot. That is “worm” or “wen.wide.vitalik.eth” are both valid names. Note that the rightmost label is the equivalent of a TLD in DNS. At the time of writing, “worm” doesn’t exist as a domain name on Ethereum mainnet, but there’s nothing in the code to prevent it from existing.

Now, there are a few caveats to human-readable names when it comes to using them on-chain. In particular, working with strings in Solidity can get messy quite fast and is also not very efficient. Using a hash function to obtain a fixed-length representation of names is therefore the obvious solution. This fixed-length representation of a name is what we call a node. Since nodes provide the internal representation of names in the ENS we capture their formal definition here.

Definition: A node is a bytes32 identifier, which is obtained from an ENS name by first normalising it according to UTS-46 and then applying the Namehash algorithm to it.

At this point, it’s not really necessary to know anything about Unicode UTS-46, but you should be aware that it exists. Among other things, the normalisation according to UTS-46 checks the names for validity (for example underscores are prohibited) and converts all names to lowercase.

However, the Namehash algorithm is the heart of the ENS and therefore we have to take a close look at it first. Fortunately for us, its definition is very compact and easy to understand by means of an example. The full scope of its definition is a bit more difficult to understand, but we will come back to it at the appropriate place and by the end of the article you should have become aware of its prominent position in the ENS.

namehash([]) = 0x0

namehash([label, …]) = keccak256(namehash(…), keccak256(label))

This pseudo-code implementation of Namehash expects a name in list form, i.e. the name is split into its labels using the dot as a separator. An example: ‘vitalik.eth’ becomes [‘vitalik’, ’eth’], ‘vitalik.wallet.eth’ becomes [‘vitalik’, ‘wallet’, ’eth’] etc. The base case for the recursion is the empty list [] for which the algorithm returns 0x0 (note: 0x0 is short for a 32 byte zero). Through recursion implemented in the second line, each label is hashed first and then, starting with the rightmost list entry, the previous calculation is concatenated with the label hash and hashed again. The most basic non-trivial example we can give is the calculation of ’eth’:

1. namehash(['eth']) = keccak256(namehash([]), keccak256('eth'))

2. namehash(['eth']) = keccak256(0x0, keccak256('eth'))

3. namehash(['eth']) = keccak256(0x0, 0x4f5b812789fc606be1b3b16908db13fc7a9adf7ca72641f84d75b47069d3d7f0)

4. namehash(['eth']) = keccak256(0x00000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000004f5b812789fc606be1b3b16908db13fc7a9adf7ca72641f84d75b47069d3d7f0)

5. namehash(['eth']) = 0x93cdeb708b7545dc668eb9280176169d1c33cfd8ed6f04690a0bcc88a93fc4ae

It’s worth highlighting that both normalisation and hashing are processes which are executed off-chain (if possible). Let’s finally move on to the actual contracts.

2.2 The ENS Registry

The core on-chain component of the ENS is the registry. This smart contract is essentially a record-keeping device. Every name at every level gets an entry here.

This entry contains the owner of the name, the associated resolver, as well as a caching time-to-live (TTL). In the actual smart contract this data is stored by mapping nodes to a struct:

struct Record {

address owner;

address resolver;

uint64 ttl;

}

mapping (bytes32 => Record) records;

Let’s look at the contract deployment and the first steps after that. The constructor is actually just one line, which saves the contract deployer as the owner of the node 0x0 in the records mapping:

constructor() public {

records[0x0].owner = msg.sender;

}

Therefore, a new ENS registry starts out with only one record attached to the node 0x0. The name “node” is no coincidence: the ENS name space follows a tree structure and 0x0 is the root node. Of course, it is not a binary tree, but each “TLD name” is a child node of 0x0. Now, let’s see how to register our first name! From the point of view of the root node every new node is a subnode, so we need to inspect the following method.

function setSubnodeOwner(bytes32 node, bytes32 label, address owner) public authorised(node) returns(bytes32) {

bytes32 subnode = keccak256(abi.encodePacked(node, label));

_setOwner(subnode, owner);

emit NewOwner(node, label, owner);

return subnode;

}

First, this function can only be called by the owner of node (guaranteed by the authorised modifier). This is a crucial point of the implementation. Before continuing let’s take a look at that modifier:

modifier authorised(bytes32 node) {

address owner = records[node].owner;

require(owner == msg.sender || operators[owner][msg.sender]);

_;

}

We can safely ignore the operators mapping for now, as it’s only used to allow another account to manage one’s node. The main takeaway is that in the default state of the contract this modifier is only passed, when the msg.sender address is registered in the owner field of node. We’ll get to the implications of this shortly.

Let’s continue with setSubnodeOwner. Alongside the parent node we also need to pass the keccak256 hash of the label, as well as the address of the intended owner of the new subnode. Note, that the first line is nothing more as calculating the Namehash of the new subnode. Since node is already namehashed we can calculate it easily in one step. This is followed by an internal call to _setOwner, which registers the new subnode for its owner:

function _setOwner(bytes32 node, address owner) internal virtual {

records[node].owner = owner;

}

As you can see, the tree structure is not explicitly captured in the records mapping. The tree hierarchy is only guaranteed by the way Namehash works and that is perfectly sufficient. This is a really elegant and resource-aware solution which serves as a good example of how blockchain development differs from traditional software development.

In fact, the tree structure encoded in names is primarily a hierarchy of access rights. Recall that the authorised modifier acts at the level of a node and not at the level of the label in question. This means that the owner of a node can use setSubnodeOwner to override any of its subnodes, even if they are not registered as the owner of those subnodes in the registry. Therefore, the owner of 0x0 has full control over all nodes.

Now, since we started from a freshly deployed ENS the only node we can pass to setSubnodeOwner is the root node 0x0. If we wanted to establish the eth subdomain we first would have to calculate its keccak256 hash,keccak256(‘eth’) = 0x4f5b812789fc606be1b3b16908db13fc7a9adf7ca72641f84d75b47069d3d7f0, and pass that as label. Technically, we would have to normalize the label first according to UTS-46, but the string “eth” is already normalized. In a real application, however, this would be a necessary first step. The owner field is necessary for handing over control over a subnode to an address that is not the ENS registry deployer address.

That’s all we need to know about the registry for now. You can find the whole source code here.

2.3 Resolvers

In order for a node to be used within ENS, a resolver must be assigned to it. This can only be done by the current owner of the node. To do this, the owner must call the setResolver method of the ENS registry and pass the node as well as the address of the new resolver.

function setResolver(bytes32 node, address resolver) public virtual override authorised(node) {

emit NewResolver(node, resolver);

records[node].resolver = resolver;

}

Resolvers commonly implement EIP-165 by providing a supportsInterface method, which lets clients discover which ENS interfaces a resolver supports. The idea is that a name in ENS can potentially be resolved to many different things (as described in the introduction) and not every resolver needs to implement every possible use case. The first example of a resolver we can give is therefore the empty resolver:

contract EmptyResolver {

function supportsInterface(bytes4 interfaceID) public pure returns (bool) {

return interfaceID == 0x01ffc9a7;

}

}

Okay, that’s maybe not very useful. A more instructive, but still quite simple example is an address resolver. In this scenario, owners of a node can link their node to an Ethereum address. Note that this info is stored in a node => address mapping on the level of the resolver and not in the ENS registry.

contract SimpleAddrResolver {

ENS ens;

mapping (bytes32 => address) addresses;

modifier authorised(bytes32 node) {

require(isAuthorised(node));

_;

}

constructor(ENS _ens) {

ens = _ens;

}

function supportsInterface(bytes4 interfaceID) public pure returns (bool) {

return interfaceID == 0x01ffc9a7 || interfaceID == 0x3b3b57de;

}

function isAuthorised(bytes32 node) internal view returns(bool) {

address owner = ens.owner(node);

return owner == msg.sender;

}

function addr(bytes32 node) public view returns (address) {

return addresses[node];

}

function setAddr(bytes32 node, address addr) external authorised(node) {

addresses[node] = addr;

}

}

However, with every request to change the mapping of a node to an address (setAddr), the ENS registry is queried for the owner of the respective node. So at this point the registry is incorporated into the process by the address resolver.

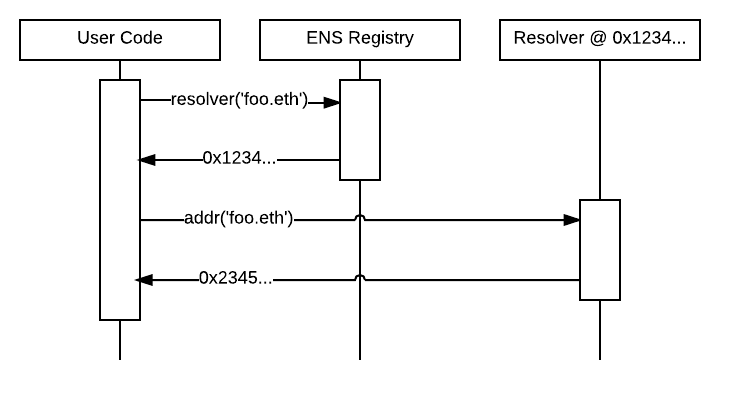

Now we are ready to understand how name to address resolution works in the ENS. The following image from the ENS docs shows the name resolution procedure for “foo.eth”. First by calling resolver we inquire the ENS registry about the responsible resolver for “foo.eth”. Afterwards, we ask the received resolver for the Ethereum address for “foo.eth” by calling addr.

A small side note: It is important to start with the name resolution at the level of the registry, because only the registry knows which resolver is currently responsible for the respective name. Even if you think you already know the correct resolver address, it may have been changed over time or it may even have been part of a phishing attack.

There are many different kinds of implementations for resolvers, which vary depending on the use case. A common extension of the address resolver mentioned above is to allow support for storing addresses of other blockchains. This way, several crypto addresses can be stored for one name at the same time. This is implemented by extending the address mapping to two variables: Given values for node and coinType it yields a bytes-type object:

mapping(bytes32 => mapping(uint256 => bytes)) addresses;

The desired coinType follows SLIP-0044 and must be specified for the name resolution. Therefore, the getter and setter methods now take the form:

function addr(bytes32 node, uint256 coinType) public view returns (bytes memory) {

return addresses[node][coinType];

}

function setAddr(bytes32 node, uint256 coinType, bytes memory a) public authorised(node) {

addresses[node][coinType] = a;

}

The EIP165 interface ID for this multicoin addr function is 0xf1cb7e06.

This concludes our introduction to resolver contracts. For further reading, the chapter on the PublicResolver from the official ENS documentation is recommended as a starting point.

2.4 Registrars

We have so far covered the two main components of the Ethereum Name Service. In the section on the registry, we saw that each node owner can in principle create as many subnodes as they wish. In practice, however, the creation of subnodes is typically managed by a smart contract, which can freely specify the conditions for acquiring a subdomain. In particular, this is the case for Top-Level Domains like “.eth”. These smart contracts are called registrars. By design, each person who owns a domain (on any level) can manage the subdomains themselves, i.e. they can also deploy and use a registrar contract for administration as they wish.

Let’s look at an example. This registrar implementation allows anyone to call register, to obtain a subnode of some fixed parent node. After a period of 4 weeks the subnode will be available for registration again.

contract TestRegistrar {

uint constant registrationPeriod = 4 weeks;

ENS ens;

bytes32 public parentNode;

mapping (bytes32 => uint) public expiryTimes;

constructor(ENS _ens, bytes32 _node) public {

ens = _ens;

parentNode = _node;

}

function register(bytes32 label, address owner) public {

require(expiryTimes[label] < block.timestamp);

expiryTimes[label] = block.timestamp + registrationPeriod;

ens.setSubnodeOwner(parentNode, label, owner);

}

}

As you can see in the last line of the register function, after checking availability the contract just calls setSubnodeOwner at the ENS registry on behalf of the user. For this to work the TestRegistrar contract must hold ownership of parentNode, i.e. the registrar’s address must have been stored in the ENS registry for parentNode.

One especially useful application of registrars is reverse resolution, that is the process of mapping an Ethereum address to an ENS name. On mainnet the ReverseRegistrar implements reverse lookup as an opt-in process. It controls the addr.reverse domain and allows any user to call its setName function in order to have their Ethereum address linked with their domain.

function setName(string memory name) public returns (bytes32) {

bytes32 node = claimWithResolver(address(this), address(defaultResolver));

defaultResolver.setName(node, name);

return node;

}

We will not go into all the implementation details here, but describe the process briefly instead. The first line of setName accomplishes two things. First, the calling account is given ownership over the associated reverse ENS record. A reverse ENS record is simply a conventional ENS record which is used for the purpose of reverse resolution. In other words, a caller with the account 0x314159265dd8dbb310642f98f50c066173c1259b afterwards owns the subdomain 0x314159265dd8dbb310642f98f50c066173c1259b.addr.reverse. Next, a special type of resolver, called a reverse resolver is set as the resolver in the reverse record. Finally, in the second line, the user’s provided name is supplied to the setName function of this reverse resolver (called defaultResolver above). The following contract is a simplified version of a reverse resolver.

contract ReverseResolver {

ENS ens;

mapping(bytes32 => string) public names;

constructor(ENS _ens) public {

ens = _ens;

}

modifier owner_only(bytes32 node) {

require(msg.sender == ens.owner(node));

_;

}

function setName(bytes32 node, string calldata _name) public owner_only(node) {

names[node] = _name;

}

}

In summary, reverse resolution works exactly like normal resolution, except that an Ethereum address is used as a label for the subdomain.

As you can see registrars offer many possibilities to use your ENS domain in creative ways. They complement the functionality of registry and resolvers and are the final part of our presentation of the ENS core contracts.

3. The Permanent Registrar

Whew! Congratulations if you have made it this far - you are already familiar with all the basic components of the Ethereum Name Service. In this final section, we’ll have a look at some cool aspects of the .eth Permanent Registrar. This is the smart contract that manages the allocation of .eth domains on the Ethereum mainnet.

3.1 .eth Domains are ERC-721 Tokens

Certainly one of the coolest features of the Permanent Registrar is that it’s fully ERC-721 compliant, i.e. second-level “.eth” domains are tradable as NFTs. According to EIP-721 the identifier of an NFT, its tokenId, must be a uint256. In the implementation of the Permanent Registrar it was decided to use the uint256 representation of the label hashes for the tokenId. Therefore, the contract uses uint256 instead of bytes32 for labels and then casts back to bytes32 when interacting with the registry. In the code snippet below you can see part of the process of registering a domain with the registrar.

function _register(uint256 id, address owner, uint duration, bool updateRegistry) internal live onlyController returns(uint) {

require(available(id));

require(now + duration + GRACE_PERIOD > now + GRACE_PERIOD); // Prevent future overflow

expiries[id] = now + duration;

if(_exists(id)) {

// Name was previously owned, and expired

_burn(id);

}

_mint(owner, id);

if(updateRegistry) {

ens.setSubnodeOwner(baseNode, bytes32(id), owner);

}

emit NameRegistered(id, owner, now + duration);

return now + duration;

}

You can also see how the mint and burn processes of the ERC-721 token are handled during (re-)registration. Maybe you also noticed the two modifiers, live and onlyController. The live modifier checks whether the current Permanent Registrar contract is still in use, while the onlyController modifier restricts access for the _register function to registered controllers. Instead of users registering or renewing a domain directly with the Permanent Registrar, this is done via separate Controller smart contracts. The controller contract registers the domain on behalf of the buyer with the Permanent Registrar and afterwards transfers full ownership to them.

3.2 Reclaiming Ownership of a Name

However, not all user requests are handled by the controller. If you somehow lose ownership over your domain’s registration at the ENS registry, but are still in possession of your ERC-721 token you can reclaim ownership of your registry records by calling the reclaim function of the Permanent Registrar.

/**

* @dev Reclaim ownership of a name in ENS, if you own it in the registrar.

*/

function reclaim(uint256 id, address owner) external live {

require(_isApprovedOrOwner(msg.sender, id));

ens.setSubnodeOwner(baseNode, bytes32(id), owner);

}

As a fully ERC-721 compliant contract the registrar also needs to store all data relevant to the NFT. The reclaim function uses _isApprovedOrOwner to check eligibility. When the check is passed a single call to setSubnodeOwner sets the record straight. The following is an excerpt of OpenZeppelin’s ERC-721 implementation as inherited by the Permanent Registrar:

// Mapping from token ID to owner address

mapping(uint256 => address) private _owners;

// Mapping from token ID to approved address

mapping(uint256 => address) private _tokenApprovals;

// Mapping from owner to operator approvals

mapping(address => mapping(address => bool)) private _operatorApprovals;

// Returns whether `spender` is allowed to manage `tokenId`.

function _isApprovedOrOwner(address spender, uint256 tokenId) internal view virtual returns (bool) {

address owner = ERC721.ownerOf(tokenId);

return (spender == owner || isApprovedForAll(owner, spender) || getApproved(tokenId) == spender);

}

4. A Small Exercise

This concludes our little excursion into the smart contracts of the ENS. I would like to dismiss you with a little voluntary exercise: While domains like “alice.eth” are ERC-721 tokens, this does not apply to their subdomains.

- Why is this the case?

- Think about how you can still convert your subdomains into NFTs. (Hint: Registrar.)

You can find a solution here in the ENS documentation.

All images are from the official ENS documentation, where you can also find more detailed information on most topics. Thanks for reading and if you found an error or have further questions please feel free to contact me.